HijackLoader Delivered via SVG files

Overview

The SonicWall Capture Labs threat research team has recently been monitoring new variants of the HijackLoader malware that are being delivered through SVG files. HijackLoader is a Windows modular loader that fetches and drops secondary payloads (stealers, backdoors, loaders) while using evasion methods like Process Doppelganging, DLL search-order hijacking, and Heaven’s Gate. The loader not only delivers second-stage payloads but also provides various modules that extend the malware’s functionality. These modules mainly serve to configure settings, bypass security mechanisms, and perform code injection and execution.

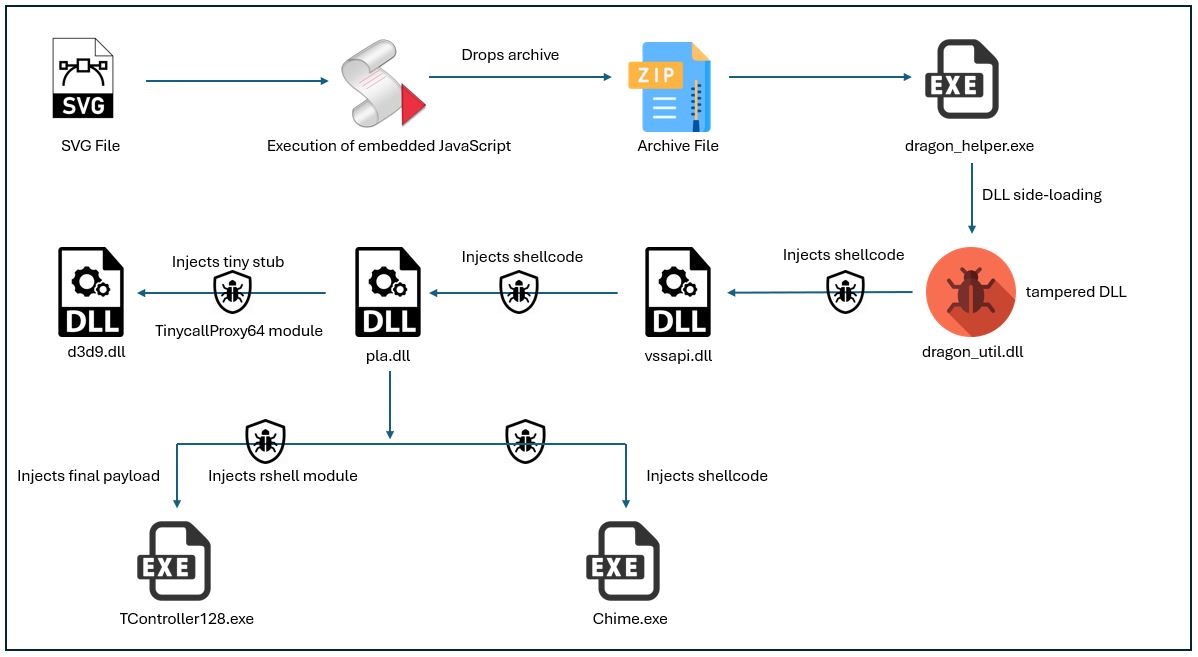

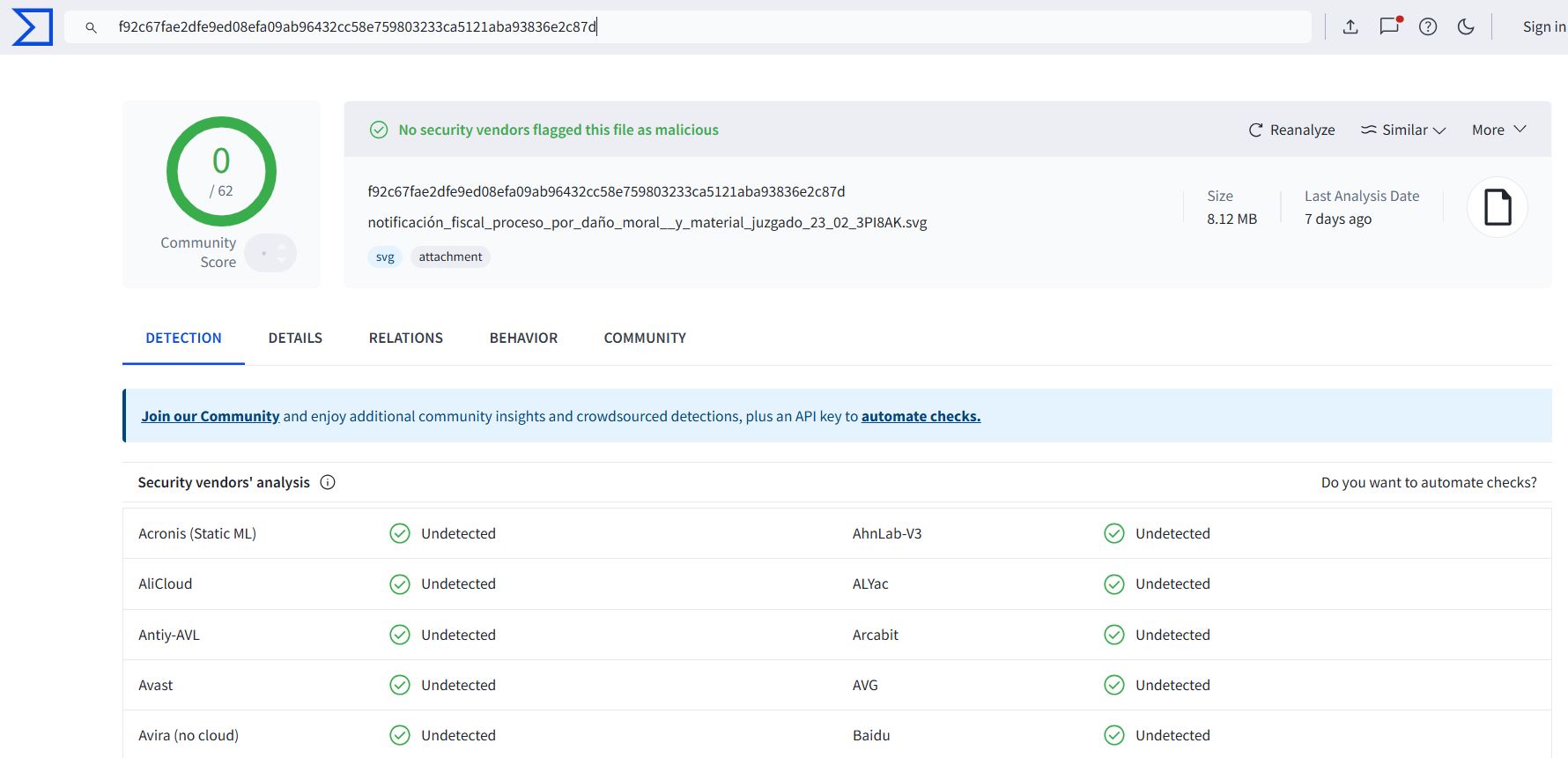

A malicious SVG file (a W3C-standard scalable vector graphic) was crafted to present a Spanish-language legal notice that encourages the recipient to click or otherwise interact with the image. The SVG includes embedded JavaScript which, upon user interaction, writes a password-protected archive to disk and displays the archive’s password in the SVG’s visible content. Because the password is shown to the user, the user is prompted to open the archive and use the revealed password to extract its contents. The extracted archive contains a malicious binary (an apparent HijackLoader). The infection chain progresses only when the user executes this binary, making the attack heavily reliant on social engineering and user participation to complete the compromise.

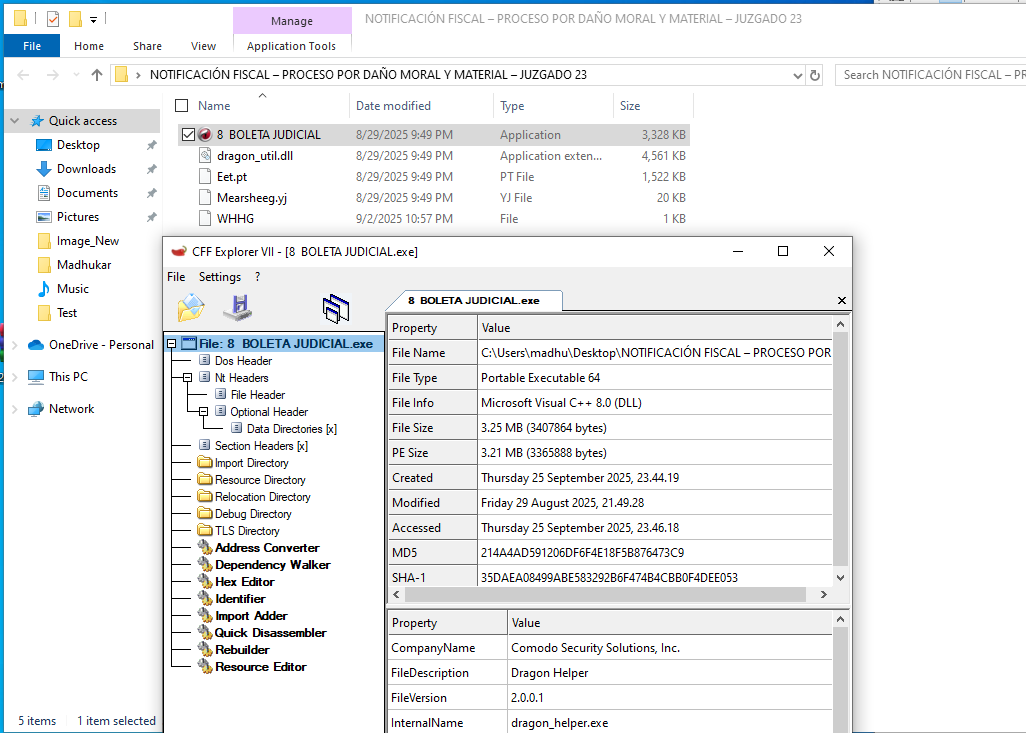

Following is the snapshot where we can observe the dropped malware package.

The extracted archive contains multiple artifacts, including dragon_helper.exe, dragon_util.dll, and an encoded shellcode blob (e.g., Eet.pt). Although dragon_helper.exe and dragon_util.dll are 64-bit components of the Comodo Dragon web-browser and bear a Comodo Security Solutions Inc. code-signing certificate (issued by Sectigo Public Code Signing CA EV R36), the dragon_util.dll in this package has been tampered with and its certificate is invalid.

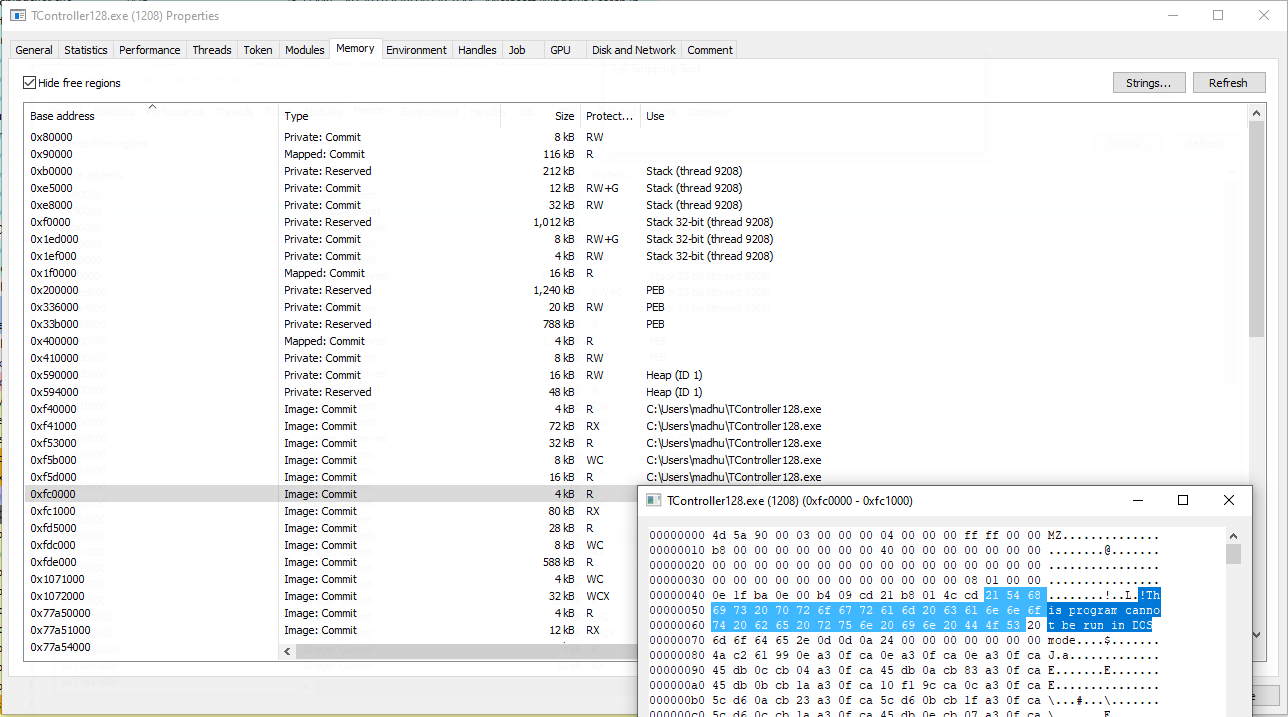

The attacker patched the DLL to enable DLL side-loading: when the apparently benign dragon_helper.exe runs, it loads the compromised dragon_util.dll, which executes embedded malicious payloads, drops signed benign files to disk (for example PDFPreviewHandlerHost.exe — which the malware renames to TController128 — and Chime.exe), and then injects code into those processes. Following the injection, PDFPreviewHandlerHost.exe connects to command-and-control (C2) servers to enable remote control and data exfiltration.

The malware renames PDFPreviewHandlerHost.exe to TController128.exe. In this blog, references to TController128.exe should be understood as PDFPreviewHandlerHost.exe; we use the malware-assigned name for clarity

The following figure presents an overview of the infection chain.

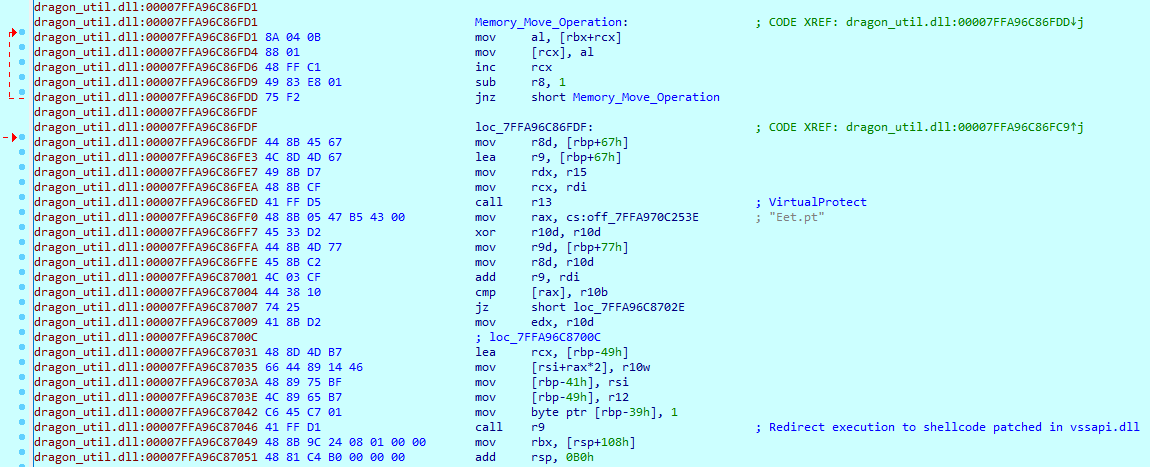

Execution transfers to the patched code inside dragon_util.dll.

The malware resolves required APIs via an API-hash routine. It opens Mearsheeg.yj (encoded shellcode blob) from the current directory and decrypts a 0x2080-byte region using a simple additive routine. The resulting decrypted buffer begins with the ASCII string vssapi.dll, immediately followed by a DWORD that specifies the size of the shellcode block destined to inject in vssapi.dll.

The malware loads vssapi.dll (Windows Volume Shadow Copy Service library) and makes its .text section writable before injecting a 0x1F1E-byte shellcode at the section start via a memory move. It restores protections with VirtualProtect and then transfers execution to the shellcode.

Execution transfers to the patched shellcode inside vssapi.dll.

API Resolution Using API Hashing Technique

The malware parses the process PEB to obtain module base addresses by walking the InLoadOrderModuleList. Those base addresses are then supplied to an API-hash resolver. The resolver is used repeatedly to resolve additional APIs required to continue the malware’s execution.

Monitor Active Antimalware Processes

The malware invokes NtQuerySystemInformation with the SystemProcessInformation class (0x05) to retrieve a snapshot of running processes, then enumerates each process entry. It computes a checksum of each process name and compares it against hard-coded DWORD hashes (notably 0x6CEA4537 for avastsvc.exe and 0x5C7024B2 for avgsvc.exe). If a match is found, the sample calls NtDelayExecution to pause execution for 45 seconds.

Decrypts the Shellcode and Patches It Into pla.dll

The malware opens Eet.pt from the current directory and applies XOR decryption to the encoded shellcode blob. The decrypted output is a compressed buffer that malware inflates via RtlDecompressBuffer. The decompressed payload contains multiple artifacts — including a module table, intermittent shellcode, benign binaries such as Chime.exe and PDFPreviewHandlerHost.exe (renamed to TController128.exe), a malware binary, and various strings, file paths, and DLL names — which the malware subsequently prepares to load into memory. This campaign leverages two apparently legitimate, digitally signed executables as part of the chain: Chime.exe (signed by Amazon.com Services LLC, issued by DigiCert Trusted G4) and PDFPreviewHandlerHost.exe (signed by FOXIT SOFTWARE INC, issued by DigiCert Trusted G4).

The malware loads pla.dll (Windows system DLL) via LoadLibraryW, modifies the .text section to be writable (PAGE_EXECUTE_READ → PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE), writes a 0x01A580-byte shellcode fragment at the section start, restores the prior memory protections using VirtualProtect, and transfers control to the patched code in pla.dll.

Execution transfers to the main shellcode inside pla.dll.

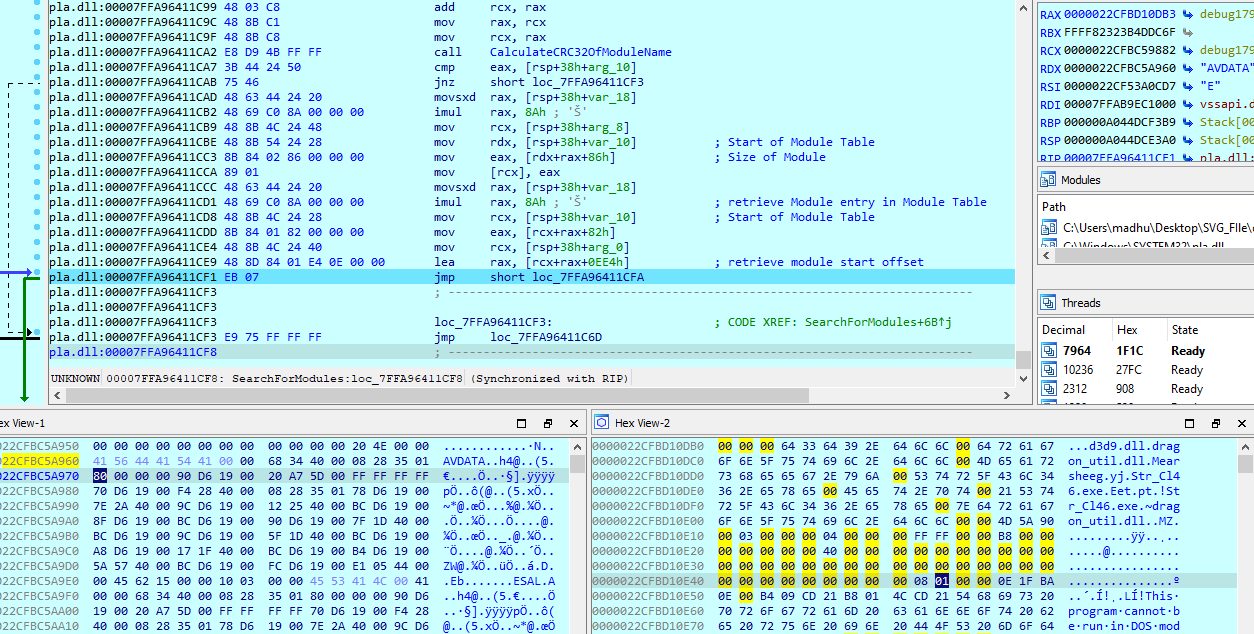

The primary shellcode is implanted into pla.dll, after which execution continues from the patched region. It dynamically resolves multiple APIs using an API-hashing algorithm to enable subsequent actions.

The HijackLoader loads a clean copy of ntdll.dll from disk and maps it using CreateFileMappingW and MapViewOfFile. It then resolves required functions from that fresh image using an API-hashing routine; those resolved functions are used in later stages to avoid potential antimalware hooks placed on the original ntdll.dll (loaded during process initialization).

The HijackLoader identifies modules in its table by computing the CRC32 of each module name and matching those values against hard-coded CRC32 entries in the payload. Each module has a specific function; for example, the AVDATA module manages a blocklist of security-product process names, with each name represented as a CRC32 hash.

Modules are organized in a structured format that includes:

- Module name

- Module offset in the table

- Module size

The module names identified in the analyzed samples are as follows:

AVDATA, ESAL, ESAL64, ESLDR, ESLDR64, ESWR, ESWR64, FIXED, LauncherLdr64, modCreateProcess, modCreateProcess64, modTask, modTask64, modUAC, modUAC64, modWriteFile, modWriteFile64, rshell, rshell64, ti, ti64, TinycallProxy, TinycallProxy64, tinystub, tinystub64, tinyutilitymodule.dll, tinyutilitymodule64.dll, SM, COPYLIST, CUSTOMINJECT, CUSTOMINJECTPATH, X64L, WDUACDATA, WDDATA, PERSDATA

The HijackLoader parses the SM module to obtain the host DLL name (d3d9.dll) for compact shellcode hosting. It locates the TinycallProxy64 module — a 0x2BA-byte, position-independent stub — then patches that stub into the retrieved target DLL. The code injection of the tiny stub is executed by changing page protections with VirtualProtect, copying the stub into place, and flushing the instruction cache with FlushInstructionCache. The stub invokes undocumented NT routines and returns to pla.dll’s patched main shellcode. The TinycallProxy64 stub is invoked repeatedly across multiple stages to perform undocumented API calls.

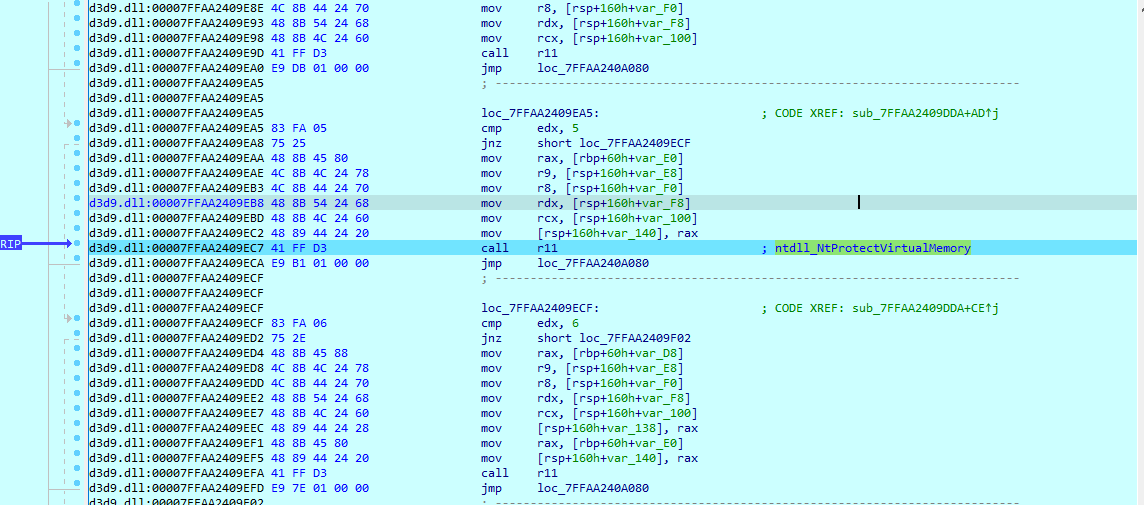

The following snapshot captures TinycallProxy64 calling an undocumented NT API.

Deployment and Persistence Mechanisms

The malware retrieves a COPYLIST module and copies artifacts — dragon_util.dll, Eet.pt, and Mearsheeg.yj — into %ProgramData%\backupExplore_Jrv1_x86. These files form the malicious components of this attack vector.

The malware sets the process working directory to %AppData%\Roaming\backupExplore_Jrv1_x86\ via SetCurrentDirectoryW, then creates a temp file (size 0x019B7FE) in the %TEMP% folder containing the encrypted shellcode and configuration info. Injected processes later read that temp file to load and execute the payload. The malware drops a .lnk shortcut in the user’s Startup folder pointing to dragon_helper.exe, which loads a malicious DLL.

Monitor Antimalware Tools

HijackLoader performs repeated checks to detect active antimalware processes on the system.

The loader invokes NtQuerySystemInformation to retrieve the process list, computes CRC32 checksums of process names, and matches them against the hard-coded value 0xF868B2F1 to identify msmpeng.exe. When msmpeng.exe is present, we observed no change in HijackLoader’s behavior.

The HijackLoader reads CRC32 values for antimalware process names from the AVDATA module, injects a 0x2BA-byte stub (TinycallProxy64) into d3d9.dll, and redirects execution to that injected code. From the injected module, it calls NtQuerySystemInformation (InformationClass = SystemProcessInformation, 0x05) to enumerate active processes, computes the CRC32 of each process name, and compares those hashes against embedded CRC32s for vendors such as Kaspersky, Avast, Bitdefender, AVG, and others. A matching hash may cause the malware to alter its execution path.

Anti-Hooking Technique

The HijackLoader loads a clean copy of ntdll.dll from disk and parses its export directory. For each exported function, it compares the first byte of the in-memory ntdll (loaded at process initialization) with the corresponding byte from the clean image. When a mismatch is detected — indicating a hook, inline patch, or a software breakpoint set by a debugger — the loader leverages a TinycallProxy64 stub to call NtProtectVirtualMemory and change the target region’s protection from PAGE_EXECUTE_READ to PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE. It then overwrites the beginning of the function in memory with the first 0x10 bytes taken from the clean ntdll disk image, effectively restoring the original prologue and bypassing userland hooks.

Parses and Executes modWriteFile64 Module

The HijackLoader XOR-encrypts the main 0x1A580-byte shellcode (shellcode in pla.dll) in temporary memory, then searches for the modWriteFile64 module.

It injects a small 0x239-byte (modWriteFile64) stub into pla.dll which performs the following actions:

- Overwrites pla.dll’s .text section (which previously hosted the main shellcode) with code copied from kernel32.dll

- Drops a benign file to disk at %AppData%\Roaming\backupExplore_Jrv1_x86\Chime.exe

- Decrypts the previously XOR-encrypted main shellcode held in memory and writes the recovered code into pla.dll’s .text section

Finally, execution control is transferred back to the main shellcode in pla.dll (the code path that earlier jumped into the 0x239-byte stub).

Parses and Executes CUSTOMINJECT Module

The HijackLoader reads the CUSTOMINJECT module (holding the in-memory PDFPreviewHandlerHost.exe binary path) and the CUSTOMINJECTPATH module (the intended disk path %USERPROFILE%\TController128.exe) and proceeds to create file C:\Users\<username>\TController128.exe on disk.

During execution of modWriteFile64 and CUSTOMINJECT, HijackLoader writes Chime.exe and TController128.exe to disk (previously extracted from the compressed buffer), launches both processes in a suspended state, and proceeds to perform code injection into each target.

Payload Decryption and Staging

The HijackLoader copies an encoded blob of size 0xAC8C8 into temporary memory and XOR-decrypts it in place to recover the final payload intended for injection into a remote process.

The loader employs two distinct injection techniques: it uses Process Doppelganging to implant the final payload into TController128.exe and performs direct shellcode injection into Chime.exe.

HijackLoader resolves the rshell and ESAL modules from its module table. These paired components coordinate to inject and execute the final payload within the remote TController128.exe process, and afterwards they remove the in-memory shellcode artifacts.

Parses and Executes modCreateProcess64 Module

The HijackLoader XOR-encrypts the main 0x1A580-byte shellcode (shellcode in pla.dll) in temporary memory, then searches for the modCreateProcess64 module.

It injects a small 0x279-byte (modCreateProcess64) stub into pla.dll which performs the following actions:

- Overwrites pla.dll’s .text section (which previously hosted the main shellcode) with code copied from kernel32.dll

- Creates TController128.exe in suspended mode

- Decrypts the previously XOR-encrypted main shellcode held in memory and writes the recovered code into pla.dll’s .text section

Finally, execution control is transferred back to the main shellcode in pla.dll (the code path that earlier jumped into the 0x279-byte stub).

Process Doppelganging

The malware creates a new transaction via NtCreateTransaction, sets it as the current transaction using RtlSetCurrentTransaction, and then creates and writes the final payload to a file (NtCreateFile → NtWriteFile). It creates a section backed by that not-yet-committed file using NtCreateSection and finally calls NtRollbackTransaction to abort the transaction, so the file never appears on disk.

The malware calls NtGetContextThread, supplying a thread handle for the TController128.exe process to retrieve its thread context. It then uses NtReadVirtualMemory to read the base address where TController128.exe is loaded in memory. It injects a 0x2BA-byte stub (TinycallProxy64 module) into d3d9.dll to call NtMapViewOfSection to map the final payload (stored in a tainted section) into the virtual address space of TController128.exe.

The following snapshot captures the final payload being mapped from the tainted section into TController128.exe (loaded at 0xFC0000) using NtMapViewOfSection.

The HijackLoader overwrites the entry-point region of the TController128.exe process with the rshell module (size 0x69CA).

HijackLoader writes a file to the %TEMP% folder that contains metadata including the final payload address, the address and size of the rshell module, the proposed image base of the final payload and additional (currently unidentified) information. In a later stage, the rshell module reads and parses this file to locate and relocate the final payload; once relocation and parsing are complete, the rshell module executes the final payload.

The loader injects a 0x2BA-byte TinycallProxy64 stub into d3d9.dll and calls NtResumeThread on the target thread to start the TController128.exe process.

It uses NtWriteVirtualMemory to zero out the first 0x400 bytes of the final payload in TController128.exe.

Execute modCreateProcess64 Module to Start Chime.exe

The HijackLoader XOR-encrypts the 0x1A580-byte main shellcode (shellcode in pla.dll) in temporary memory, locates the modCreateProcess64 module, and injects a 0x279-byte (modCreateProcess64) stub into pla.dll. The stub performs the same sequence of actions previously used when creating TController128.exe, except that here the loader creates Chime.exe in a suspended state. The HijackLoader initiates its remote code injection routine targeting the Chime.exe process.

Section-Mapping Injection (NtCreateSection / NtMapViewOfSection)

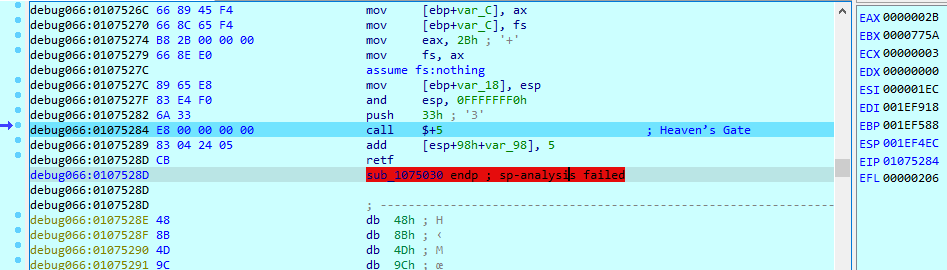

HijackLoader opens the 32-bit version of pla.dll with CreateFileW and creates a section for the file using NtCreateSection with SECTION_ALL_ACCESS (0xF001F) as an argument. It then calls undocumented NT APIs via the TinycallProxy64 stub, maps the section backed by pla.dll into Chime.exe with NtMapViewOfSection and obtains the mapped base address. After acquiring the base address of pla.dll in the Chime.exe process, the malware overwrites pla.dll’s .text section with a 0xF24D-byte shellcode using NtWriteVirtualMemory.

The malware retrieves the Chime.exe thread context (RtlWow64GetThreadContext), updates the thread’s instruction pointer to the patched code (RtlWow64SetThreadContext) and resumes the thread (NtResumeThread) via the TinycallProxy64 module.

The Chime process spawns PowerShell and adds the directory containing the running HijackLoader to Microsoft Defender’s exclusion list.

The TController128.exe process reaches out to the hard-coded C2 server IP 192.159.99.232:4448 to fetch commands and exfiltrate data.

The following snapshot shows the injected payload in TController128.exe using the Heaven’s Gate technique.

After successfully injecting code into two different processes using two distinct techniques, dragon_helper.exe self-terminates.

Evasion Techniques Observed in This Variant

- Process Doppelganging and Section-Mapping Injection

- DLL search-order hijacking

- Heaven’s Gate

- API hashing technique to resolve each API address dynamically

- Payload and shellcode decrypted using simple XOR and additive routines

- DWORD hash used to find the next-stage module in the modules table (e.g., AVDATA for detecting antimalware processes)

- Blocklist of process-name hashes

- Stack-string formation for each DLL name before invoking the LoadLibraryW API

- Shellcode patched into system DLLs (e.g., pla.dll, vssapi.dll, and d3d9.dll) and executed from those libraries to evade detection

- NtDelayExecution used to impose timed delays across stages, likely to hinder dynamic analysis and evade sandboxing

The following snapshot shows that the SVG files were not detected by the antimalware product.

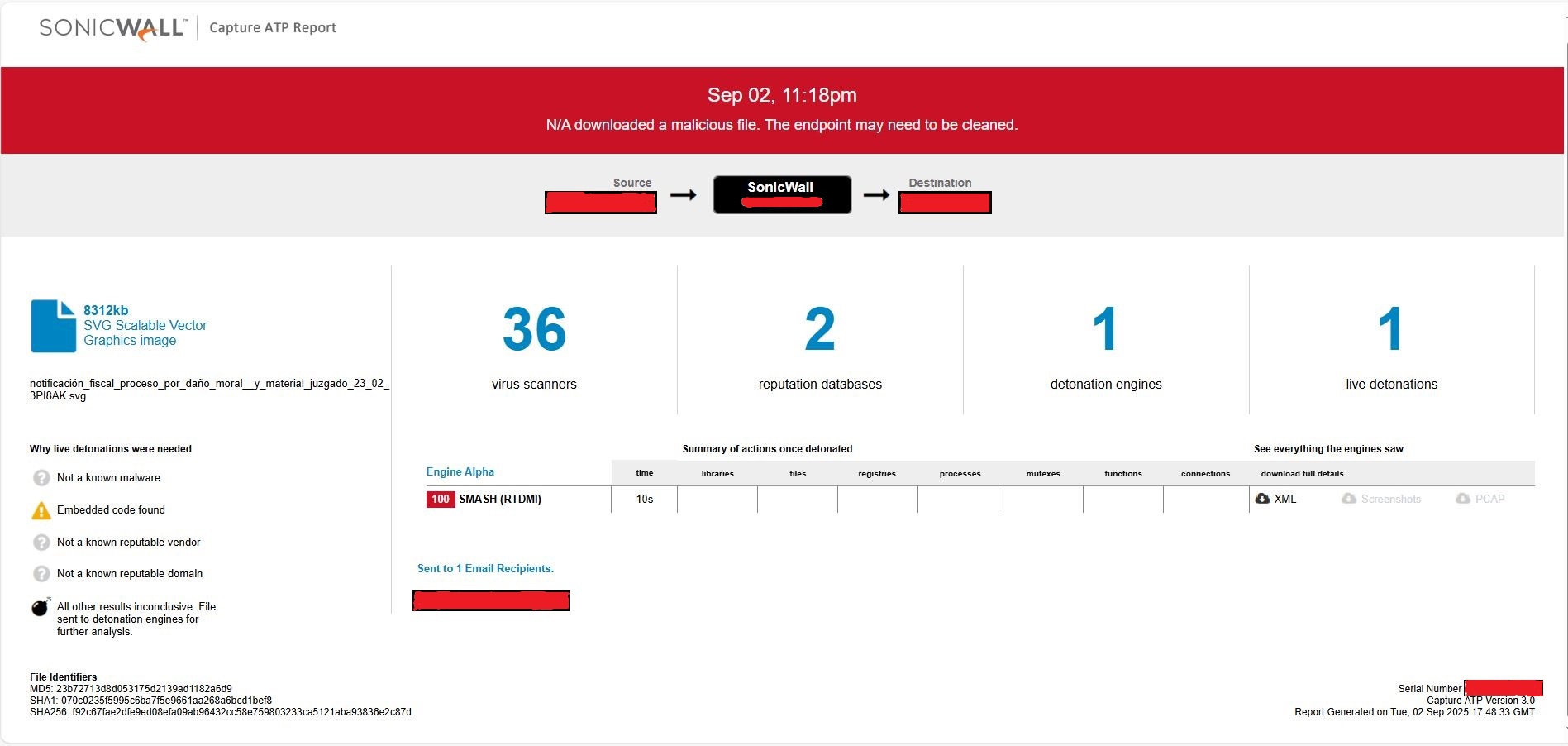

This threat can also be detected by SonicWall Capture ATP with Real-Time Deep Memory Inspection (RTDMI™). Below is the snapshot showing the detection details.

Conclusion

HijackLoader’s modular architecture supports continually refined evasion tactics aimed at defeating detection. By implanting compact shellcode stubs inside legitimate system DLLs, it obscures malicious behavior from antimalware products. We assess it will keep rolling out new modules designed to increase analysis difficulty and detection resistance.

IOCs

| SR No | Sample Description | SHA256 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SVG File | f92c67fae2dfe9ed08efa09ab96432cc58e759803233ca5121aba93836e2c87d |

| 2 | Password Protected Archive File (Password: 89G4UYYT) | 7730eb8eb3728e2192570204b0c0ea1019dc63c1c65d5188bd711f0f2603f7d6 |

| 3 | dragon_helper.exe (clean file) | 4c51bc3a44b63bd7104998d7d473edcd4acca8165b4b6a16ebbc5101146ca989 |

| 4 | dragon_util.dll (malware DLL) | 82b19747645326479e2068fe08d850e1696e021f39fdf1a71874fe91b71fbee5 |

| 5 | PDFPreviewHandlerHost.exe (clean file renamed as TController128.exe) | 36ecf37aaa72e402f55fda4530854b34390ed78b4ff933f25fbaf769c1aaf357 |

| 6 | Chime.exe (clean file) | adb8347dfa1b1df1ca2211fe4d7e82f27ced939f1bf3d52548e52bc9e23fc52c |

| 7 | Eet.pt (encoded shellcode blob) | f562ee8a770865c86d0d3bdabd5968f1164a2fde91f538c3beb6e6b18063cf6f |

| 8 | Mearsheeg.yj (encoded shellcode blob) | b02b56277afab343a7566571fc84ab596c7b1a37f3c50aceba9ed48118235d35 |

| 9 | Final payload injected in TController128.exe | dac93dfd8c68df93ec710d481c2cd530c3f9cb4f0ab0d82953ed63fb313044de |

Share This Article

An Article By

An Article By

Madhukar Waghmare

Software Dev Senior Engineer

Madhukar Waghmare

Software Dev Senior Engineer